Interlude in the Gori Ganga Valley : Munsiari and Ralam

The quest for the meaning of human life is something that has plagued ordinary people and philosophers alike for millenia. I am similarly bothered as the jeep begins to climb the Shivaliks towards Munsiari, a good 300 km away, from the train station at Kathgodam. The station is located at the point where the Gaula river debouches from the Himalayas to densely populated alluvial plains, and we have travelled over two days and nights from Bangalore. I begin to wonder at the human condition as I look at the broad river glisten at a distance in the morning sun, and the endless towers of fissured earth being continuously uplifted as the Himalaya. Is it fatigue that awakens you to this question?

The question continues to come up as we reach Munsiari that evening, past driving rain and minor landslides. The Panchachuli pentatops present themselves spectacularly in the fading light. The sense of wonder and awe in seeing the mountain that is part of the human condition. Munsiari is a quiet town, usually an outpost even for the interprid tourist, but the next day sees us applying for permits to go on the trek to Ralam Glacier, and return via the traditional Tibetan trading route in the Milam valley. The question on the human condition arises again, with a sour note this time, as the official tasked with issuing permits asks for more paperwork. “Sensitive Border Area”. “Lives at Risk in the Remote Himalaya”. Sigh. Why do borders carve up non-existent lines across mountains? Rhetorical question, I tell myself, as we go on a flurry of activity to get the extra photographs and photocopies from the nearby photo printer, an innovation in Munsiari since I last visited in 2009. Ramnarayan and Malika, of Himal Prakriti, the organization that put together our Milam trek then, help us this time as well. In our meeting before we leave for the trek, we hear of various other changes that are have happened, are happening or due to happen in the Gori Valley – the planned hydroelectric power projects, a road linking Milam and Munsiari, the state of schools, politics of jungle ownership, the role of women in the local village society, the flow of rivers in Himalayan geological history.

I begin the trek with disappointment when I see Jhimi Ghat, where we camped on our Milam trek, in a state of being blasted for a mountain road to link Munsiari and Milam. Piles of rubble extend right up to the stream banks along the steep valley, clogging the channel in parts. Dynamiting and JCBs alternate in carving up the mountainside where we saw over thirty or more vultures roosting two years back. The hitherto peaceful village is dusty. We end the day climb to camp at Paton village, the winter home of the Ralam villagers. There are few people here, as most have migrated to the short summer in Ralam. These villagers are migrants from the neighbouring Dharma valley, and are ethnically and lingustically distinct from their neighbours in the Bhui village. Apparently the secured the land ownership rights to Ralam village and its van panchayat from the residents of Bhui in 1964. But they have been moving between Ralam and Paton for atleast seven or eight generations, as recalled by living memory. The walk up to Paton is refreshing, we cross the Gori near Lilam and then have lunch at a stream, where we encounter our only amphibian of the trip, a spectacular mottled green frog, horsetails and spiders await in webs just a foot above the flowing water. Our camp is above the Paton village, in grazing land abutting the village school. The stunning sedimentary beds in the ridges on the other side of the valley raises the question again – we are in an ancient realm, far older than civilization. I feel like an intruder.

We pass fairly dense forest the next morning, as we cross the ridge from Paton, a north-facing moist woodland, dominated by atleast two if not three species of Maple, same numbers of Oak, an understory of Rhododendron and a sprinkling of conifers in the upper reaches. The trees grow in thickness and girth as we move further in, and the understory is a vivid stranglehold of aroids, ferns, lycopods, and astonishing array of fungi. The last of the rhododendrons are in flower. The dead trees rot in the forest and are part of this landscape, with woodpeckers and barbets aplenty in the old growth. This forest and others in the valley beyond belong to the Ralam Van Panchayat. The van panchayats are a system in Uttarakhand where the local forests are communally owned by the village and administered by an elected body. The Ralam van panchayat is one of the largest in the state and controls sizable areas of deciduous and coniferous woodland, and alpine grassland across a steep elevation gradient. Our walk on the second day reveals the gradient as we ascend and descend ridges in a seemingly endless series before we end up at Lingurani. The campsite is named after the abundance of Lingu, the circinate young leaf of a fern, edible when fried in butter and salt. The good sites are already occupied by an American group, and we have to make do with sites that are also favoured by goats and rainwater as the evening progresses! The redeeming feature of the campsite are the massive horse chestnut trees, all in bloom.

We pass fairly dense forest the next morning, as we cross the ridge from Paton, a north-facing moist woodland, dominated by atleast two if not three species of Maple, same numbers of Oak, an understory of Rhododendron and a sprinkling of conifers in the upper reaches. The trees grow in thickness and girth as we move further in, and the understory is a vivid stranglehold of aroids, ferns, lycopods, and astonishing array of fungi. The last of the rhododendrons are in flower. The dead trees rot in the forest and are part of this landscape, with woodpeckers and barbets aplenty in the old growth. This forest and others in the valley beyond belong to the Ralam Van Panchayat. The van panchayats are a system in Uttarakhand where the local forests are communally owned by the village and administered by an elected body. The Ralam van panchayat is one of the largest in the state and controls sizable areas of deciduous and coniferous woodland, and alpine grassland across a steep elevation gradient. Our walk on the second day reveals the gradient as we ascend and descend ridges in a seemingly endless series before we end up at Lingurani. The campsite is named after the abundance of Lingu, the circinate young leaf of a fern, edible when fried in butter and salt. The good sites are already occupied by an American group, and we have to make do with sites that are also favoured by goats and rainwater as the evening progresses! The redeeming feature of the campsite are the massive horse chestnut trees, all in bloom.

The next day sees us awake to open skies. We are cold from the previous night, and Angshu has part of sleeping bag drenched in a puddle. Amiti wakes to fifteen bearded goats staring at her. We decide to move on and save a rest day for a later date. The rain does not relent, but the mind does. I wonder at the human condition again. Why am I fascinated by the flowers and the birds? Why do I need an explanation for this fascination? Is there a hidden moral dilemma that this fascination is a deeply selfish action, uncaring about another’s questions and interests? I also wonder at the way the mind works when fascinated, I do not feel the weight of my bag and the rain when I see an interesting flower, or the flurry of Mrs.Gould’s Sunbirds feeding on a Berberis clump at 3000 m, or a spectacular waterfall on a sheer cliff. But the bag weighs on my mind, and back, otherwise. We camp at Kildam, another regular stop for sheep. Dhiraj,Yattu, and Prahlad, part of our kitchen-guide-porter crew, conjure up hot soup and dinner as the night recovers from the day’s rain and cold. Kailash, another crew member, gives me a clear quartz crystal that he found on our steep descent to Lingurani. He reminds me of someone, and upon query, I realize that his brother Tillu had accompanied us on the trek to Milam two years back. I wake up the next morning with the moon rising over the ridge above the campsite.

The next day sees us awake to open skies. We are cold from the previous night, and Angshu has part of sleeping bag drenched in a puddle. Amiti wakes to fifteen bearded goats staring at her. We decide to move on and save a rest day for a later date. The rain does not relent, but the mind does. I wonder at the human condition again. Why am I fascinated by the flowers and the birds? Why do I need an explanation for this fascination? Is there a hidden moral dilemma that this fascination is a deeply selfish action, uncaring about another’s questions and interests? I also wonder at the way the mind works when fascinated, I do not feel the weight of my bag and the rain when I see an interesting flower, or the flurry of Mrs.Gould’s Sunbirds feeding on a Berberis clump at 3000 m, or a spectacular waterfall on a sheer cliff. But the bag weighs on my mind, and back, otherwise. We camp at Kildam, another regular stop for sheep. Dhiraj,Yattu, and Prahlad, part of our kitchen-guide-porter crew, conjure up hot soup and dinner as the night recovers from the day’s rain and cold. Kailash, another crew member, gives me a clear quartz crystal that he found on our steep descent to Lingurani. He reminds me of someone, and upon query, I realize that his brother Tillu had accompanied us on the trek to Milam two years back. I wake up the next morning with the moon rising over the ridge above the campsite.

Ralam is the only settlement in the Ralam valley. We camp the next day at Marjhali, a few kilometers before the village. A landslide had destroyed the regular road and we cross a large, recent landslide and a tongue of old snow across the river, climb a ridge and reach Marjhali. Another species of rhododendron is in full bloom, the plant is much shorter and the flowers are larger, mauve instead of red. There is a speckled moth that reminds me of Biston betularia in the shade of a rock on the landslide. Horsetails and marsh marigolds sparkle along streams. A Golden Eagle flies overhead. Birch woodland begins and ends. Red-billed Choughs circle in flocks. We are in the alpine zone.

The Ralam river cuts deep in the valley, braiding on the river bed before the monsoon excess changes the shade and turbulence of the waters. Angshu, Anirudh and Abhimanyu make a snow man from snow collected on the hillside above the campsite. We come across sheep everywhere. The alpine sheep are curious creatures, they may let you pass quietly but as Maria discovered, might also just gently crash into the backside to indicate their presence! We spend a lazy afternoon before heading off early the next day to Ralam Glacier. Theo, also part of Himal Prakriti, joins us as he did the previous day from Kildam to Marjhali, and continues to offer valuable information and insights into the Himalayas. He tells us the story of yaks in Ralam that he helped get from Ladakh via Tibet several years back. We could see the yaks at a distance across the valley. He and Chander, one of the Ralam villagers, come along with us towards the glacier. The land is covered with juniper bushes and Cotoneaster shrubs. Streams enroute have Primulas, Caltha and Veronicas in dense huddles of white, yellow and blue. Potentilla atrosanguniea carpeted the floor of the grazing slopes with bloody blooms. Closer to the terminal moraine are dwarf willows in flower. Its a dry and desolate landscape; the long moraines on the laternal flanks of the glacier, the brown terminus of the ice flow, the river gushing out, the glistening snow and ice on the mountains above, all remind me of my own insignificance. The beauty is overwhelming.

Shane finds a fossil. Its a bivalve imprint fossil on shale. This part of the Himalaya was under the Tethys sea before India collided with Asia, and many fossilized creatures have since then been upfolded into mountains several thousand meters up. The finding of the fossil reminds me of the discovery of the Burgess shale, except that Shane, who is also Canadian, does not have a horse at the time of the discovery nor is the fossil as ancient as the Cambrian fossils found in British Columbia. Shane and Chaiti have accompanied us on the trek, and are an essential part of our group. They push us up when we are down (literally!), help us across snow slides, advise us on trip rations and liaise with the crew. They are warm and large-hearted people, like our crew, like the mountain people we meet wherever we went, like Theo, Mallika and Ram.

We sleep early on returning from the glacier. The next day, we have to cross the Burjikanj pass so an early start is essential. An exceptionally fine day on the glacier is not predictive of weather in subsequent days. We huddle and talk about our mental states. Mental states matter in steep climbs, and can make a significant difference to the quality of the climbing experience. Also, the weather is something we will be working against, so we need to be in top mental form. All of us. We decide that the slow climbers go first, the others follow. And so we begin at 5 AM, cross over to near Ralam, meet Chander who is there to show the way, and start climbing at 0730. It is 1130 when we reach the top at 4567 meters, after crossing increasingly smaller gentians and primulas, fewer birds, some treacherous ground, good weather and almost no snow. The other side of the ridge is deep in snow. We can see the large Milam glacier at a distance, and the two peaks of Nanda Devi and Nanda Devi East on a closer ridge across the valley. It is an exerting climb, and after a quick lunch we begin the descent after saying goodbye to Chander. He has to return to Ralam to plant out potatoes and other vegetables. In the short summer in Ralam, every day in the field counts and it is Chander’s third day with us. We need his knowledge of the lay of the land, and his wife need his hand in the fields.

Our initial descent of the first 200m or so of the slope is at 50 or 60 kmph – we slide down the 50 degree slope, an unforgettable experience that many of us want to repeatedly renew – we slide and climb back a few meters and slide again! The fatigue of the morning is soon forgotten. But the skies begin to darken and we have to move on. We make a difficult descent through steep slopes and deep snow, bordered by dwarf, fragrant rhododendron krummolz. The threat of rain is made real as we manage to set up camp at Bharmatganj, overlooking the Gori Ganga and Milam glacier at a distance. I revisit my question on the human condition. I don’t feel particularly exhilarated that I crossed the pass. I was more inquisitive of the primulas, genitians and the dwarf rhododendron krummolz. Is the motivation to cross the pass to see these plants, or be responsible for a group of children from Bangalore? Is the motivation for people in the Ralam valley to know the path on the pass to collect a valuable fungus that might net them thousands of rupees or for some other reason? In camp, huddled in the tent and talking shop with Shruthi and Abhimanyu, the answer isn’t immediately clear.

A steep descent along an alpine meadow and skirting the Gori brought us to Tola, a village that is partly in ruins. We are enroute to Martoli across the valley and stop here for lunch. There is a blue-fronted redstart nesting in a hollow in the ruins. A neatly lined nest with three chicks. We also see house buntings, and begin to see several species of warblers. The Eurasian cuckoo calls at a distance and flocks of Snow Pigeon and Hill Pigeon hurtle across the windy valley. It is interesting to note that every turn in the path can mean the difference between being in flower or not; aspect, as well as elevation, have a critical influence on vegetation in the Himalaya – the thickest forests are north-facing.

Martoli is at 3400 meters, a quiet village in the Milam Valley that comes alive once a year in October for a Nanda Devi festival. Milam and the surrounding mountains have been open to mountaineers and trekkers only since 1993 when permits were first issued to travel in the Milam valley. It is currently a fairly well-visited valley for trekkers, and part of an ancient trading route to Tibet. After the hostilities with China in 1962, the route was closed an trading ceased. The trader communities stopped visiting these villages and the supporting farmer families found the short summers and harsh landscape less inviting. The villages slowly swept into decrepitude. Martoli is a typical example of such a village. We spend the evening and the next day resting and exploring the village and the birch forest. The forest yields a few flowering dwarf rhododendrons, flowering strands of the similar but unrelated Guizotia and Cassiope, isolated patches of Marchantia, horsetails and a purple orchid amidst Primulas along a stream. We meet several visitors at the local hotel – an old couple and their son heading back to Munsiari, a couple of German nanotech students enroute to Milam, a Bengali family enroute to the Nanda Devi base camp. Everyone has a story to say, everyone offers interpretations of the human condition. Our crew gave a wildly entertaining version on the evening of our arrival. The Bengali family praying at the Nanda Devi temple before their departure is another version.

Abhimanyu and Angshu outdo themselves and make another snow man, complete with arms of sticks and a discarded bidi stub and glasses for style.The snow man is soon dismantled and come in handy in a snow brawl a few minutes later. By now, many of us are sun-burnt, or mildly numb in the toes and fingertips due to frost bite. The wind dies down with the sun, and we sleep a quiet night. The next day is the long walk to Bugdiyar and we descend sharply at Rilkote and Mapang. The cliffs are high and steep and stunning. Forest and sheer cliffs and landslides compete for attention. The path goes quite close to the river, and with the drop in elevation, the humidity increases. We pass glacier-cut cliffs and sharp descents of the river to reach Bugdiyar at 2500 meters by evening and camp by the riverside. The river washes up rounded pebbles of varied colour and texture, a testament to the complex geology of the Himalaya. We are confronted by mating pairs of Plumbeous redstarts and an active nest with three eggs of the Grey Wagtail. The last day of the walk was through humid forests and some open areas closer to Lilam. We encounter Munna, also part of our previous trek crew. He now works for one of the companies involved in surveying the Bugdiyar site for a run-of-the-river power project. This involves a series of small dams on the river to divert the water into tunnels running through the mountainside and running turbines. Fact remains that this is a seismically active area, and that the river carries enormous amounts of silt weathered by the glaciers and eroded by rain – either way the turbines will be choked sooner than later. But the river bed will dry up. The lifeline of the people in the valley will no longer exist.

Abhimanyu and Angshu outdo themselves and make another snow man, complete with arms of sticks and a discarded bidi stub and glasses for style.The snow man is soon dismantled and come in handy in a snow brawl a few minutes later. By now, many of us are sun-burnt, or mildly numb in the toes and fingertips due to frost bite. The wind dies down with the sun, and we sleep a quiet night. The next day is the long walk to Bugdiyar and we descend sharply at Rilkote and Mapang. The cliffs are high and steep and stunning. Forest and sheer cliffs and landslides compete for attention. The path goes quite close to the river, and with the drop in elevation, the humidity increases. We pass glacier-cut cliffs and sharp descents of the river to reach Bugdiyar at 2500 meters by evening and camp by the riverside. The river washes up rounded pebbles of varied colour and texture, a testament to the complex geology of the Himalaya. We are confronted by mating pairs of Plumbeous redstarts and an active nest with three eggs of the Grey Wagtail. The last day of the walk was through humid forests and some open areas closer to Lilam. We encounter Munna, also part of our previous trek crew. He now works for one of the companies involved in surveying the Bugdiyar site for a run-of-the-river power project. This involves a series of small dams on the river to divert the water into tunnels running through the mountainside and running turbines. Fact remains that this is a seismically active area, and that the river carries enormous amounts of silt weathered by the glaciers and eroded by rain – either way the turbines will be choked sooner than later. But the river bed will dry up. The lifeline of the people in the valley will no longer exist.

We reach Munsiari tired and wet. Binaji, mine and Srini’s hostess for the rest of our stay in Shankdura village, makes us feel at home with our first baths in ten days and a hot meal of rotis and subzi. The next day, we meet the women of the Maati collective at Sarmoli village, and hear their experiences of running homestays and include visitors like us as part of their otherwise busy lives. They also speak of their work as a collective, the experiences and politics of working with the van panchayat, male domination in the society, the impact of liqour on their lives. In living with them for a few days and promising to transport some rajma to Bangalore, we feel good at being part of their lives.

We reach Munsiari tired and wet. Binaji, mine and Srini’s hostess for the rest of our stay in Shankdura village, makes us feel at home with our first baths in ten days and a hot meal of rotis and subzi. The next day, we meet the women of the Maati collective at Sarmoli village, and hear their experiences of running homestays and include visitors like us as part of their otherwise busy lives. They also speak of their work as a collective, the experiences and politics of working with the van panchayat, male domination in the society, the impact of liqour on their lives. In living with them for a few days and promising to transport some rajma to Bangalore, we feel good at being part of their lives.

I leave Munsiari with the same unanswered, perhaps futile question – the meaning of human existence. I haven’t understood it any better, but perhaps I can put it in perspective – the Himalayas, its resilient people, the turbulent rivers, the captivating flora, the fine group of children that I went with – all contribute to the question, its very personal, present and future statements and meanings.

~ Thejaswi

At CFL, our melas have been a chance to collectively delve into diverse realms of exploration. Melas occur every two years. We choose a theme we would like to explore and in smaller groups, adults and children immerse themselves in a six-month long process where we follow ideas, embrace the unfamiliar,engage in a learning that allows for play and imagination.

At CFL, our melas have been a chance to collectively delve into diverse realms of exploration. Melas occur every two years. We choose a theme we would like to explore and in smaller groups, adults and children immerse themselves in a six-month long process where we follow ideas, embrace the unfamiliar,engage in a learning that allows for play and imagination. It was a time of learning about life on and around these trees. It was a time which awakened us to details we were barely aware of. It was a time where we encountered both unexpected surprises as well as periods of restlessness when minds find it difficult to be present in stillness. The question of what it means to pay attention both to the surrounding world as well as to the inner one was a primary focus during this mela.

It was a time of learning about life on and around these trees. It was a time which awakened us to details we were barely aware of. It was a time where we encountered both unexpected surprises as well as periods of restlessness when minds find it difficult to be present in stillness. The question of what it means to pay attention both to the surrounding world as well as to the inner one was a primary focus during this mela. Students and teachers worked on themes of interest, understanding chosen areas through their own senses as well as with guidance. People learned about a range of areas. Leaf-fall patterns, ant diversity and behavior, grasses, the life of the bark, canopy maps were a few themes. We shared a glimpse of our learning and fascination on a Mela Day at the end of November.

Students and teachers worked on themes of interest, understanding chosen areas through their own senses as well as with guidance. People learned about a range of areas. Leaf-fall patterns, ant diversity and behavior, grasses, the life of the bark, canopy maps were a few themes. We shared a glimpse of our learning and fascination on a Mela Day at the end of November.

We pass fairly dense forest the next morning, as we cross the ridge from Paton, a north-facing moist woodland, dominated by atleast two if not three species of Maple, same numbers of Oak, an understory of Rhododendron and a sprinkling of conifers in the upper reaches. The trees grow in thickness and girth as we move further in, and the understory is a vivid stranglehold of aroids, ferns, lycopods, and astonishing array of fungi. The last of the rhododendrons are in flower. The dead trees rot in the forest and are part of this landscape, with woodpeckers and barbets aplenty in the old growth. This forest and others in the valley beyond belong to the Ralam Van Panchayat. The van panchayats are a system in Uttarakhand where the local forests are communally owned by the village and administered by an elected body. The Ralam van panchayat is one of the largest in the state and controls sizable areas of deciduous and coniferous woodland, and alpine grassland across a steep elevation gradient. Our walk on the second day reveals the gradient as we ascend and descend ridges in a seemingly endless series before we end up at Lingurani. The campsite is named after the abundance of Lingu, the circinate young leaf of a fern, edible when fried in butter and salt. The good sites are already occupied by an American group, and we have to make do with sites that are also favoured by goats and rainwater as the evening progresses! The redeeming feature of the campsite are the massive horse chestnut trees, all in bloom.

We pass fairly dense forest the next morning, as we cross the ridge from Paton, a north-facing moist woodland, dominated by atleast two if not three species of Maple, same numbers of Oak, an understory of Rhododendron and a sprinkling of conifers in the upper reaches. The trees grow in thickness and girth as we move further in, and the understory is a vivid stranglehold of aroids, ferns, lycopods, and astonishing array of fungi. The last of the rhododendrons are in flower. The dead trees rot in the forest and are part of this landscape, with woodpeckers and barbets aplenty in the old growth. This forest and others in the valley beyond belong to the Ralam Van Panchayat. The van panchayats are a system in Uttarakhand where the local forests are communally owned by the village and administered by an elected body. The Ralam van panchayat is one of the largest in the state and controls sizable areas of deciduous and coniferous woodland, and alpine grassland across a steep elevation gradient. Our walk on the second day reveals the gradient as we ascend and descend ridges in a seemingly endless series before we end up at Lingurani. The campsite is named after the abundance of Lingu, the circinate young leaf of a fern, edible when fried in butter and salt. The good sites are already occupied by an American group, and we have to make do with sites that are also favoured by goats and rainwater as the evening progresses! The redeeming feature of the campsite are the massive horse chestnut trees, all in bloom. The next day sees us awake to open skies. We are cold from the previous night, and Angshu has part of sleeping bag drenched in a puddle. Amiti wakes to fifteen bearded goats staring at her. We decide to move on and save a rest day for a later date. The rain does not relent, but the mind does. I wonder at the human condition again. Why am I fascinated by the flowers and the birds? Why do I need an explanation for this fascination? Is there a hidden moral dilemma that this fascination is a deeply selfish action, uncaring about another’s questions and interests? I also wonder at the way the mind works when fascinated, I do not feel the weight of my bag and the rain when I see an interesting flower, or the flurry of Mrs.Gould’s Sunbirds feeding on a Berberis clump at 3000 m, or a spectacular waterfall on a sheer cliff. But the bag weighs on my mind, and back, otherwise. We camp at Kildam, another regular stop for sheep. Dhiraj,Yattu, and Prahlad, part of our kitchen-guide-porter crew, conjure up hot soup and dinner as the night recovers from the day’s rain and cold. Kailash, another crew member, gives me a clear quartz crystal that he found on our steep descent to Lingurani. He reminds me of someone, and upon query, I realize that his brother Tillu had accompanied us on the trek to Milam two years back. I wake up the next morning with the moon rising over the ridge above the campsite.

The next day sees us awake to open skies. We are cold from the previous night, and Angshu has part of sleeping bag drenched in a puddle. Amiti wakes to fifteen bearded goats staring at her. We decide to move on and save a rest day for a later date. The rain does not relent, but the mind does. I wonder at the human condition again. Why am I fascinated by the flowers and the birds? Why do I need an explanation for this fascination? Is there a hidden moral dilemma that this fascination is a deeply selfish action, uncaring about another’s questions and interests? I also wonder at the way the mind works when fascinated, I do not feel the weight of my bag and the rain when I see an interesting flower, or the flurry of Mrs.Gould’s Sunbirds feeding on a Berberis clump at 3000 m, or a spectacular waterfall on a sheer cliff. But the bag weighs on my mind, and back, otherwise. We camp at Kildam, another regular stop for sheep. Dhiraj,Yattu, and Prahlad, part of our kitchen-guide-porter crew, conjure up hot soup and dinner as the night recovers from the day’s rain and cold. Kailash, another crew member, gives me a clear quartz crystal that he found on our steep descent to Lingurani. He reminds me of someone, and upon query, I realize that his brother Tillu had accompanied us on the trek to Milam two years back. I wake up the next morning with the moon rising over the ridge above the campsite.

Abhimanyu and Angshu outdo themselves and make another snow man, complete with arms of sticks and a discarded bidi stub and glasses for style.The snow man is soon dismantled and come in handy in a snow brawl a few minutes later. By now, many of us are sun-burnt, or mildly numb in the toes and fingertips due to frost bite. The wind dies down with the sun, and we sleep a quiet night. The next day is the long walk to Bugdiyar and we descend sharply at Rilkote and Mapang. The cliffs are high and steep and stunning. Forest and sheer cliffs and landslides compete for attention. The path goes quite close to the river, and with the drop in elevation, the humidity increases. We pass glacier-cut cliffs and sharp descents of the river to reach Bugdiyar at 2500 meters by evening and camp by the riverside. The river washes up rounded pebbles of varied colour and texture, a testament to the complex geology of the Himalaya. We are confronted by mating pairs of Plumbeous redstarts and an active nest with three eggs of the Grey Wagtail. The last day of the walk was through humid forests and some open areas closer to Lilam. We encounter Munna, also part of our previous trek crew. He now works for one of the companies involved in surveying the Bugdiyar site for a run-of-the-river power project. This involves a series of small dams on the river to divert the water into tunnels running through the mountainside and running turbines. Fact remains that this is a seismically active area, and that the river carries enormous amounts of silt weathered by the glaciers and eroded by rain – either way the turbines will be choked sooner than later. But the river bed will dry up. The lifeline of the people in the valley will no longer exist.

Abhimanyu and Angshu outdo themselves and make another snow man, complete with arms of sticks and a discarded bidi stub and glasses for style.The snow man is soon dismantled and come in handy in a snow brawl a few minutes later. By now, many of us are sun-burnt, or mildly numb in the toes and fingertips due to frost bite. The wind dies down with the sun, and we sleep a quiet night. The next day is the long walk to Bugdiyar and we descend sharply at Rilkote and Mapang. The cliffs are high and steep and stunning. Forest and sheer cliffs and landslides compete for attention. The path goes quite close to the river, and with the drop in elevation, the humidity increases. We pass glacier-cut cliffs and sharp descents of the river to reach Bugdiyar at 2500 meters by evening and camp by the riverside. The river washes up rounded pebbles of varied colour and texture, a testament to the complex geology of the Himalaya. We are confronted by mating pairs of Plumbeous redstarts and an active nest with three eggs of the Grey Wagtail. The last day of the walk was through humid forests and some open areas closer to Lilam. We encounter Munna, also part of our previous trek crew. He now works for one of the companies involved in surveying the Bugdiyar site for a run-of-the-river power project. This involves a series of small dams on the river to divert the water into tunnels running through the mountainside and running turbines. Fact remains that this is a seismically active area, and that the river carries enormous amounts of silt weathered by the glaciers and eroded by rain – either way the turbines will be choked sooner than later. But the river bed will dry up. The lifeline of the people in the valley will no longer exist. We reach Munsiari tired and wet. Binaji, mine and Srini’s hostess for the rest of our stay in Shankdura village, makes us feel at home with our first baths in ten days and a hot meal of rotis and subzi. The next day, we meet the women of the Maati collective at Sarmoli village, and hear their experiences of running homestays and include visitors like us as part of their otherwise busy lives. They also speak of their work as a collective, the experiences and politics of working with the van panchayat, male domination in the society, the impact of liqour on their lives. In living with them for a few days and promising to transport some rajma to Bangalore, we feel good at being part of their lives.

We reach Munsiari tired and wet. Binaji, mine and Srini’s hostess for the rest of our stay in Shankdura village, makes us feel at home with our first baths in ten days and a hot meal of rotis and subzi. The next day, we meet the women of the Maati collective at Sarmoli village, and hear their experiences of running homestays and include visitors like us as part of their otherwise busy lives. They also speak of their work as a collective, the experiences and politics of working with the van panchayat, male domination in the society, the impact of liqour on their lives. In living with them for a few days and promising to transport some rajma to Bangalore, we feel good at being part of their lives.

The landscapes were varied and wide: some breathtaking in their beauty and others striking in their filth. Beginning at an erstwhile trading town, Kharepatan, on the southern bank of the Vaghotan river, in Maharashtra, we walked and boated along the Vaghotan through verdant farmlands and garbage-lined shores, over vast ghostly, grassy cliff -tops. We waded through wet river streamlets, criss-crossed the river in a boat, swam in its waters but mostly, walked along its banks for fifty-five kilometres till we reached its mouth at the Arabian Sea in Vijaydurg.

The landscapes were varied and wide: some breathtaking in their beauty and others striking in their filth. Beginning at an erstwhile trading town, Kharepatan, on the southern bank of the Vaghotan river, in Maharashtra, we walked and boated along the Vaghotan through verdant farmlands and garbage-lined shores, over vast ghostly, grassy cliff -tops. We waded through wet river streamlets, criss-crossed the river in a boat, swam in its waters but mostly, walked along its banks for fifty-five kilometres till we reached its mouth at the Arabian Sea in Vijaydurg. Now turning south, we walked about eighty-five kilometres from Vijaydurg to Malvan along the Arabian sea; along her white sandy beaches and in her glass-like waters; up and down her headlands;sometimes flanked in foliage and at other times rocky or covered in a carpet of golden grass. Here too, as we moved further south, we noticed more evidence of human presence – garbage washed up along the high-tide lines.

Now turning south, we walked about eighty-five kilometres from Vijaydurg to Malvan along the Arabian sea; along her white sandy beaches and in her glass-like waters; up and down her headlands;sometimes flanked in foliage and at other times rocky or covered in a carpet of golden grass. Here too, as we moved further south, we noticed more evidence of human presence – garbage washed up along the high-tide lines. All along our way, we received the hospitality of many people – everyone from migrant labourers from Karnataka, to local residents and people in hotels and lodges where we stayed. It was a humbling experience.

All along our way, we received the hospitality of many people – everyone from migrant labourers from Karnataka, to local residents and people in hotels and lodges where we stayed. It was a humbling experience.

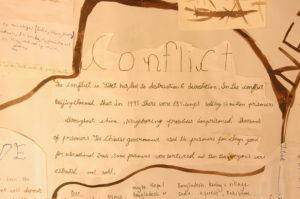

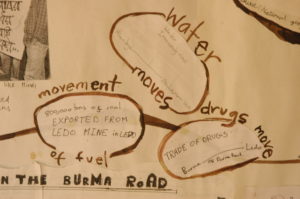

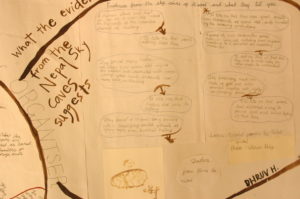

Over the span of CFL’s life, a diverse array of projects have happened in the middle school. These projects broadly fall into the areas of science and social science. As part of our thinking about these courses, we have tried to pay attention to curricular goals, skills, approaches and themes. In all projects, we value the possibilities that “direct contact” opens. These may be in the form of working with data in a lab or learning about a place and people through interaction.

Over the span of CFL’s life, a diverse array of projects have happened in the middle school. These projects broadly fall into the areas of science and social science. As part of our thinking about these courses, we have tried to pay attention to curricular goals, skills, approaches and themes. In all projects, we value the possibilities that “direct contact” opens. These may be in the form of working with data in a lab or learning about a place and people through interaction.

ldren will now move on to other projects and other engagements. The glimpses they have encountered of lives they had little contact with earlier may fade and perhaps appear at a later time. This may have been the only instance where our children hand-wrote a letter to a farther land. Some of them may feel drawn to handwriting another letter, some time.

ldren will now move on to other projects and other engagements. The glimpses they have encountered of lives they had little contact with earlier may fade and perhaps appear at a later time. This may have been the only instance where our children hand-wrote a letter to a farther land. Some of them may feel drawn to handwriting another letter, some time.

in 1619 and are known as the

in 1619 and are known as the

Meetings in Motaganahalli

Meetings in Motaganahalli We talked about caste and access to resources, such as water and electricity. We talked about the presence of gender bias. We discussed the impact of mechanisation of labour and about what

We talked about caste and access to resources, such as water and electricity. We talked about the presence of gender bias. We discussed the impact of mechanisation of labour and about what